The Switch to Organic Cotton

In 1991, Patagonia commissioned an environmental assessment of its production. It found that the supply chains had a significant negative environmental impact. Cotton production in particular was causing environmental damage through the use of insecticides, herbicides and defoliators. In response, founder Yvon Chouinard decided to switch to organic cotton, even though the cost of organic cotton at the time was 50% to 100% higher. After competitors also switched to organic cotton too, prices relaxed, and a new market was created.

Now Patagonia is attempting the same thing with organic hemp. The company began using hemp back in 1997, and recently, they have ramped up production and introduced a range of hemp-based clothing. Will this help create a new market for organic hemp fabric?

The Decline and Comeback of Hemp

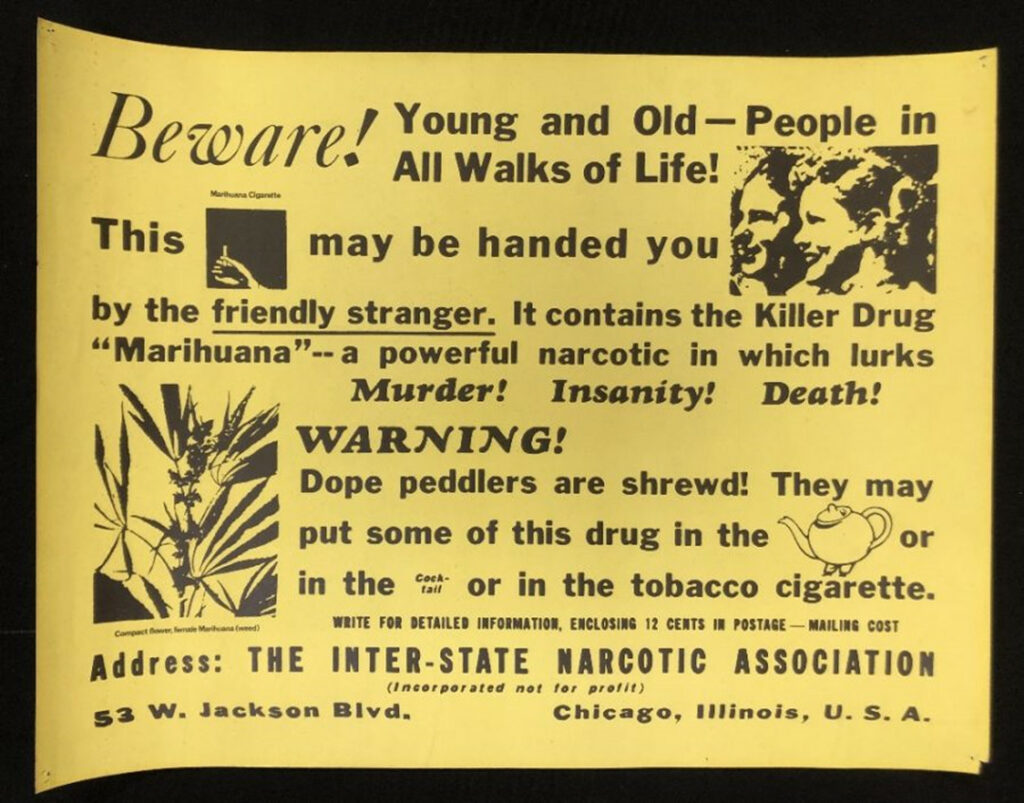

Hemp was likely the first plant cultivated by humans for making textiles, and it has a long history of use for ship’s sails, rope and clothing. The word “canvas” is derived from “cannabis”. Hemp fabric is strong, non-irritating, non-toxic and biodegradable. The plant itself can be grown without irrigation, low fertiliser usage and little to no pesticides (1). Unfortunately, hemp’s association with its black-market cousin led to its decline. The 1937 Marijuana Tax Act in America was signed by Roosevelt to impose heavy taxes on the sale of “marihuana”, and hemp production virtually ceased.

Later in 1970, the Controlled Substances Act (2) placed cannabis in the schedule 1 category, the most tightly restricted category for drugs that are “not safe to use, even under medical supervision”. This led to the further restriction of hemp in the USA. Thankfully, the Hemp Farming Act of 2018 (3) removed hemp from the schedule 1 controlled substances list and made it an ordinary agricultural product.

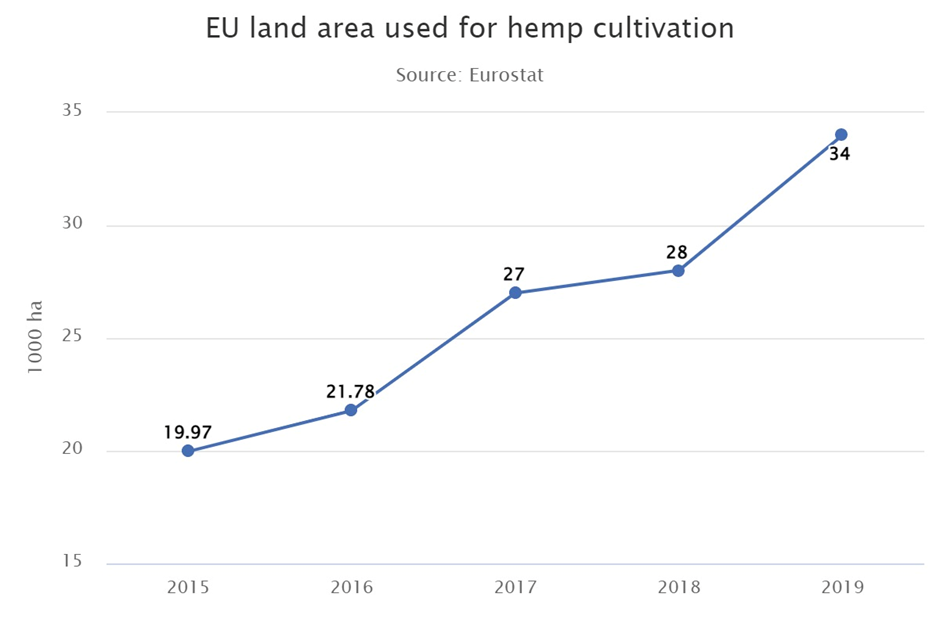

Meanwhile, in Europe, the decline of hemp was due to the introduction of other fibres like cotton, (which was cheaper, lighter, and softer), and synthetic textiles like polyester. France never prohibited hemp, but in 1960 the land under hemp dropped to its lowest recorded levels – 700 hectares. Hemp cultivation and processing was labour intensive, so it was rarely profitable. Today, France is the third largest producer in the world and the main producer in Europe. Over half of the land dedicated to hemp in Europe is in France. The EU is encouraging the production of sustainable hemp fibre as part of the EU Strategy for Sustainable Textiles (4) and the European Green Deal (5).

Source: European Commission (6).

Hemp Vs Cotton

Hemp grows vigorously and generally out-competes weeds, so the need for herbicides is minimal. No major pests impact hemp currently, so pesticides are likewise not relied on. Switching to organic is therefore relatively easy.

A 2010 study into the environmental footprint of hemp versus cotton outlined the advantages of organic hemp (7). Cotton cultivation relies heavily on defoliators, pesticides, herbicides and artificial fertilisers. 11% of the world’s agrochemicals are used for cotton, while only using 2.4% of the world’s arable land. Additionally, almost 10,000 litres of water are needed to grow and process 1kg of cotton, and in areas with low rainfall, this deficit must be made up with irrigation. This places strain on water supplies in arid regions. Roughly 73% of cotton is grown using irrigation. The depletion of the Aral Sea in Kazakhstan was partly caused by diverting the river away for rice and cotton production.

Because hemp requires less water, it’s a more sustainable choice for arid regions. Trials in Britain estimated that 300–500 litres of water are needed to grow 1kg of dry matter, while roughly 2,000 litres are required overall to produce 1 kg of usable fibre from a hemp crop. Traditional hemp processing requires 343 litres per kg of useful hemp fibre. Therefore, it’s reasonable to expect some reductions in water use if the production technique can be refined.

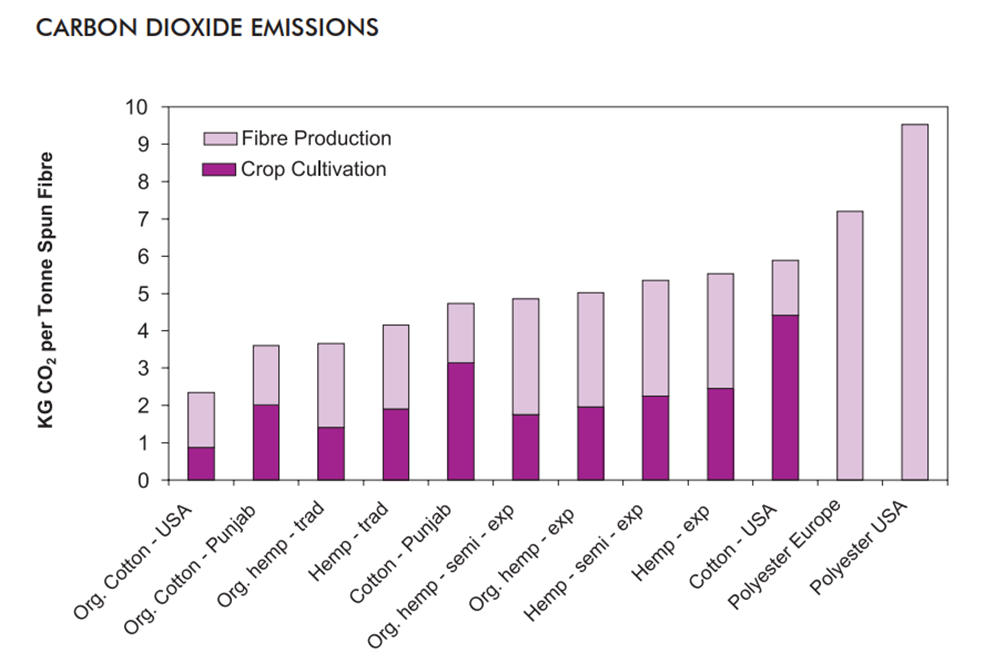

While the above graph places organic cotton as the lowest emitter of CO2, the high water consumption of cotton may make organic hemp the more sustainable option. While polyester doesn’t require land, agrochemicals or much water to produce, it emits high amounts of CO2 and is responsible for microplastic pollution.

Avoiding Microplastics

Synthetic fibres like polyester and acrylic are major sources of microplastic pollution. The microplastics are released from clothes mainly in washing machines, and find their way into rivers, oceans, and soil, where they accumulate in living organisms. The consequences of this are not yet fully understood. Read our article on microplastics to learn more.

Switching to plant-based fabrics is one way to avoid microplastic pollution. Trying to remove these fibres from water bodies or soil is impractical, so the best way to combat the problem is to prevent them from being released in the first place.

Patagonia’s Lack of Transparency

While Patagonia’s efforts to make its products more sustainable are commendable, it’s best to keep in mind that it’s partly a marketing strategy. While Patagonia claims 100% organic cotton is used in their products, their monitoring systems are internal, and therefore are vulnerable to corruption and collusion (6). Patagonia’s clothing certification is not under any pressure from the public or regulations to maintain transparency or legitimacy.

Why don’t we have a trusted, independent watchdog to investigate and verify the sustainability claims of companies? Private companies are audited for financial legitimacy, but claims of sustainability are left to the whims of marketing teams and are often misleading.

For contrast, consider the pharmaceutical industry, which is highly regulated by the FDA, ICH and in Ireland, the HPRA. These regulatory bodies impose strict rules and guidelines on drug production. Every stage is tightly regulated, from development, to formulation, production, and marketing. The process involves rigorous clinical testing and continuous market surveillance. The regulations attempt to prevent the prioritisation of profit over patient health, and presumably help protect the companies from lawsuits. This level of regulation is to be expected when the risk to people’s health is so apparent. Unfortunately, when it comes to the health of the planet, and therefore the future health of humanity, the desire for regulation seems painfully lacking.

Jack Coffey is from Cork and graduated from University College Cork in 2018 with a degree in Applied Plant Biology, with a specialty in Camellia sinensis physiology. He later went on to pursue a postgrad in Bio Pharmaceuticals. You can follow him on LinkedIn.

References

- Ranalli, P. and Venturi, G., 2004. Hemp as a raw material for industrial applications. Euphytica, 140(1), pp.1-6.

- Controlled Substances Act

- Hemp Farming Act

- EU Strategy for Sustainable Textiles

- European Green Deal

- Hemp production in the EU

- Barrett, J., Chadwick, M. and Chadwick, M., 2010. Ecological footprint and water analysis of cotton, hemp and polyester.